The Ides of March in Ancient Rome

March 15, 44 BCE

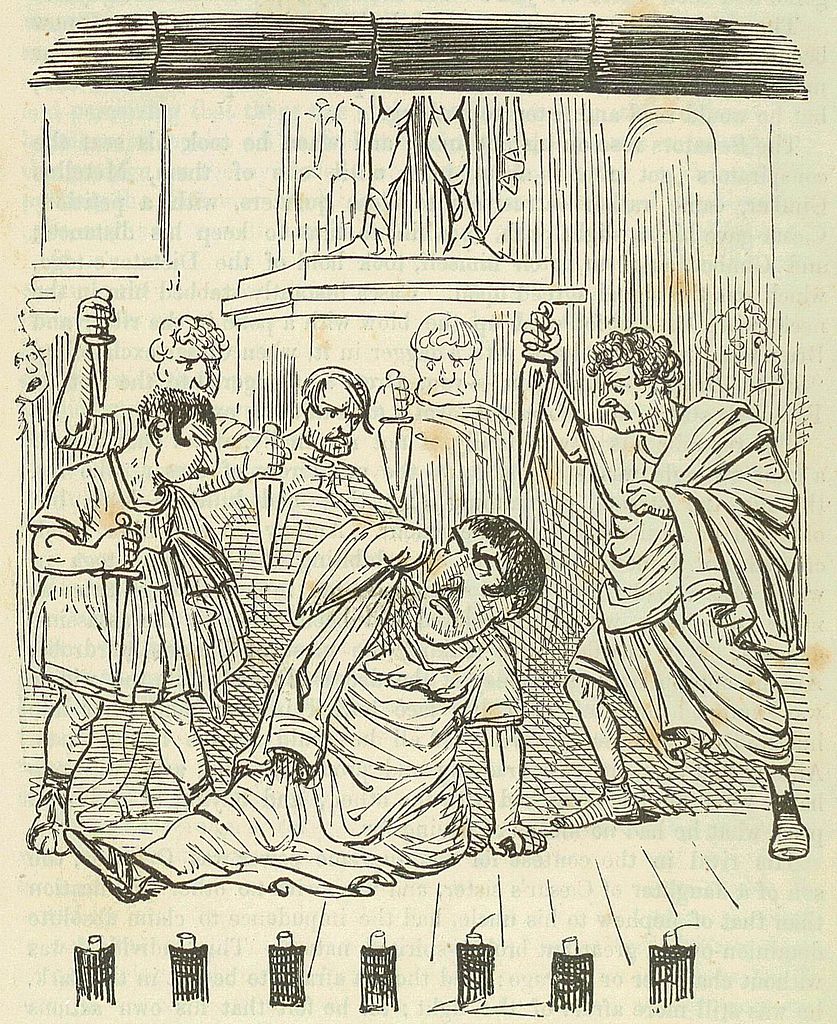

The Assassination of Julius Caesar

“Beware the Ides of March!” says the soothsayer to Julius Caesar in Shakespeare’s play, but the warning failed to take. On March 15, 44 BCE (the “Ides” is the 15th day of the month), a group of 60 members of the Roman Senate, led by Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus — better known to history as Brutus and Cassius — ambushed Caesar and stabbed him 23 times.

Born into an aristocratic family, Gaius Julius Caesar had been intimately involved in the intrigues and bloodshed that marked the last century of the Roman Republic. Torn by a bitter rivalry between the traditionalist Optimates and the reformist Populares, Rome several times descended into civil war. In that environment, the young Caesar won a major military award, the Civic Crown (a crown of oak leaves, often seen in portraits of Caesar), survived kidnapping by pirates, served in the war against Spartacus, administered Spain, and was elected Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of the Roman religion.

As a member of the Populares, Caesar made bitter enemies among the Optimates, and survived only through making an alliance with Pompey the Great and Crassus, known to history as the First Triumvirate. Caesar was elected consul in 59 BCE, and following his consulship, arranged to gain command in southern France, from which he launched his conquest of Gaul.

His enemies continued to intrigue against him. His ally in the First Triumvirate, Crassus, died on a military campaign in the east, and his other partner, Pompey the Great (married to Caesar’s daughter), changed sides after the death of his wife, because of his growing jealousy of Caesar’s accomplishments. The Optimates arranged to have Caesar stripped of power, but instead Caesar crossed the Rubicon River and civil war broke out.

Caesar was triumphant in the Civil War, defeating Pompey and his long-time enemy Cato — although he took some time off to romance the Egyptian queen Cleopatra. Returning to Rome, Caesar was appointed Dictator, a traditional office, with the goal of reforming the dysfunctional Roman government. He carried out land reforms, calendar reforms, built public works, and made constitutional changes. He extended his dictatorship several times, eventually being named Dictator in Perpetuity.

His next goal was to conquer the Parthian Empire, whose forces had killed his old partner Crassus. As he prepared to leave on his next military campaign, a group of conspirators known as the Liberatores began to plot an end to Caesar’s rule. Luring Caesar to Pompey’s Theater, the conspirators surrounded Caesar. A man named Casca struck first. As Caesar struggled to get away, eyes blinded by blood, the assassins continued to stab him until he died.

There is no evidence that Caesar actually said, “Et tu, Brute?” It was, however, a particularly important betrayal. Brutus’s mother had been Caesar’s mistress, and some have suggested that Brutus was actually Caesar’s son — though Caesar would only have been 15 at the time.

Although the Liberatores expected that they would be honored and that traditional Rome would be restored, they would be bitterly disappointed. Caesar’s death led to the final civil war of the Roman Republic. After 13 years of war, Caesar’s nephew and heir Octavian ended up sole ruler of Rome, and is thus considered the first emperor of the Roman Empire.

The illustration “The End of Julius Caesar” is by John Leech, from The Comic History of Rome by Gilbert Abbott Beckett, London:Bradbury, Evans & Co., 1850s.