The Fourth of July

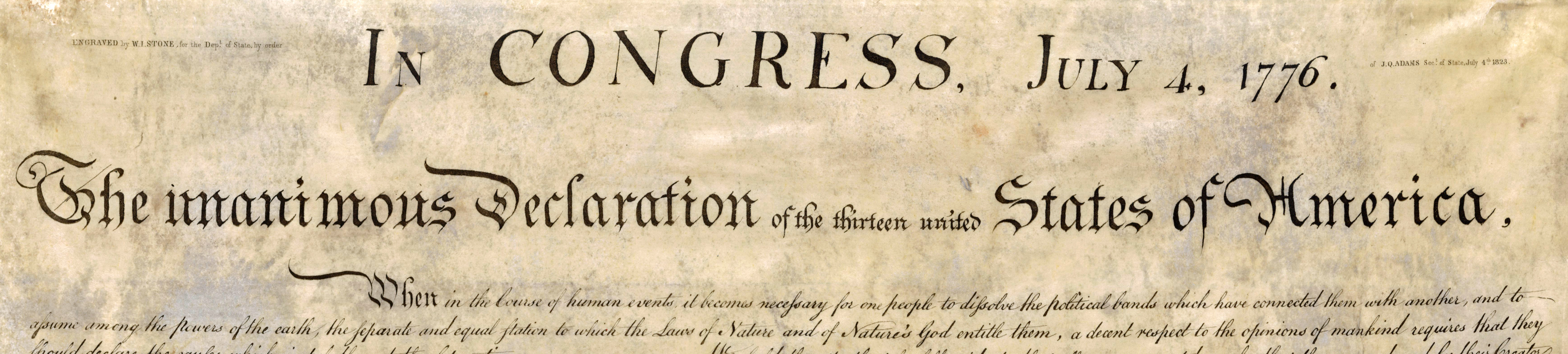

Quick — what day did the Thirteen Colonies declare their independence from Great Britain? The answer isn’t what you probably think. The Continental Congress unanimously approved the independence resolution on July 2, 1776. It was two days later, on July 4, that the Congress got around to passing the official announcement in the form of the United States Declaration of Independence.

No less than John Adams, author of the preamble (“When in the course of human events…”) and subsequently third President of the United States, urged that July 2, not 4, be celebrated. He wrote,

“The second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epocha in the history of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated by succeeding generations as the great anniversary festival. It ought to be commemorated as the day of deliverance, by solemn acts of devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forevermore.”

Adams notwithstanding, popular sentiment quickly established the ratification of the Declaration of Independence on July 4 as America’s national birthday. (Although the Declaration was passed on July 4, it wasn’t actually signed until August 2.) Perhaps it was influenced by the very prominent “July 4, 1776” at the top of the Declaration.

By the time the Declaration of Independence passed, the Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain had already been at war for more than a year. After increasing tumult and civil unrest dating back to 1763, the first actual military engagement of the war came on April 19, 1775, in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, both in Massachusetts, ending in American victory in both battles.

There was still substantial sentiment in the Colonies for reconciliation with Great Britain. A Second Continental Congress began meeting in Philadelphia in May 1775. (The First Continental Congress the previous year had only established a boycott of British goods and a petition to King George III.)

The Second Continental Congress was far from unanimous in wanting independence. Most would have been satisfied by some concessions from the British government, but George III and his advisors were in no mood to placate the unruly colonists.

In fact, most colonial delegations had no authority to vote for independence, and many delegates had to lobby their own states for permission. The first part of the Declaration of Independence, the preamble authored by John Adams, was passed on May 15, with four colonies voting against it.

On June 11, Congress authorized a “Committee of Five”: John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, New York’s Robert Livingston, and Connecticut’s Roger Sherman to draft a full declaration. Jefferson wrote the first draft, modified it based on input from the other four, and on June 28, the Declaration of Independence moved to the floor of Congress. Formal debate began on July 1, and the following day independence was approved.

There was a lot of editing left to do, and Congress cut about a fourth from the committee’s draft, and on July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was approved and sent to the printer.

American Independence Day, more commonly called simply the Fourth of July, is celebrated with fireworks, parades, concerts, baseball games, and political ceremonies. As a midsummer holiday, it’s also an occasion for barbecues and family reunions. Because of the extra holiday, the first week of July is one of the busiest travel periods of the year.

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who were the only signers of the Declaration to later serve as president, both died on the Fourth of July, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of American independence.

(P.S. It’s also my wedding anniversary.)