November 2nd in Comics, Science Fiction, and Media History

In alphabetical order…

Irwin Allen

June 12, 1916 — November 2, 1991

Director and producer, “Master of Disaster

Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea, movie and TV series

TV Series:

Lost In Space

The Time Tunnel

Land of the Giants

Lois McMaster Bujold

November 2, 1949 —

Writer, Vorkosigan, Chalion, and Sharing Knife series.

Steve Ditko

The pioneering comic artist Steve Ditko is best known as co-creator of Marvel heroes Spider-Man and Doctor Strange, but did so much more — co-creating the Charlton Comics hero Captain Atom, inspiration for The Watchmen’s Dr. Manhattan, as well as such strange characters as the Creeper and Mr. A (an Ayn Rand superhero).

Ditko, born November 2, 1927, is a reclusive man who’s given few interviews since the 1960s. He has been inducted into both the Jack Kirby Hall of Fame and the Will Eisner Hall of Fame. Ditko is of Slovak descent, from Johnstown, Pennsylvania. As a child during World War II, he built wooden models of German airplanes to aid aircraft spotters, and enlisted in the Army in 1945. While stationed in Germany, he drew comics for an Army newspaper. After his service, he enrolled at the Cartoonist and Illustrators School in New York City, drawn there by his idol Jerry Robinson, the Batman artist who created the Joker.

After a few early sales, he began working for Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, co-creators of Captain America, initially as an inker, before moving to Charlton Comics in 1954, where he created Captain Atom. (I got into trouble in elementary school after I got my schoolbus driver to turn around because I’d left a Captain Atom comic at the bus stop — I told him it was a schoolbook I’d left behind. I remember the comic vividly to this day, although it ended up the property of my elementary school principal.)

|

| Charlton’s Captain Atom |

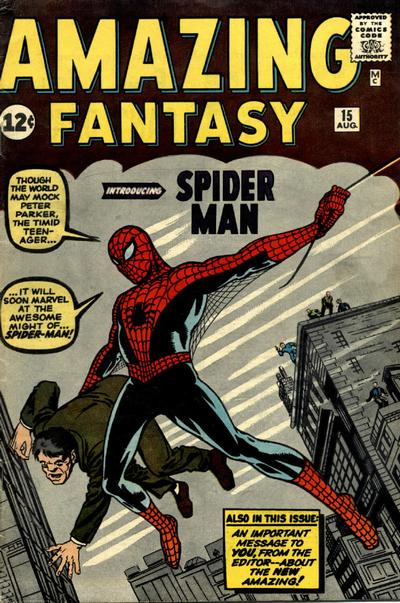

Ditko contracted tuberculosis in 1954 and returned to his parents’ home in Pennsylvania to recuperate. In late 1955, he returned to New York and began drawing for Marvel’s precursor, Atlas Comics, where he drew back-of-the-book features in his notably surreal style. These proved so popular that a new title, Amazing Fantasy (subtitled “The magazine that respects your intelligence”), was created to feature them.

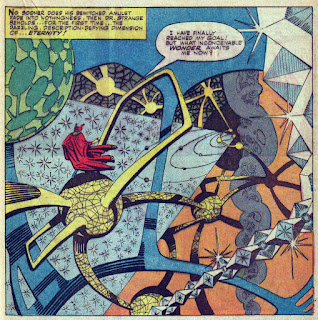

The 15th and final issue of Amazing Fantasy featured the first appearance of an “ordinary teen” superhero named Spider-Man. Although Jack Kirby had originally been tapped to draw the character, Marvel editor-in-chief Stan Lee found his portrayal “too heroic,” and turned to Steve Ditko for the job. Spider-Man was an immediate hit, and after his premier in Amazing Fantasy, quickly got his own title. Ditko’s other famous Marvel character, Doctor Strange, premiered in 1963’s Strange Tales #110.

|

| The psychedelic stylings of Ditko’s Doctor Strange |

The reasons Steve Ditko left Marvel have never been revealed. After his Marvel tenure, he worked for DC and Charlton, and for various smaller publishers. As of 2012, Steve Ditko continues to work at his Manhattan studio.

|

| Self-portrait |

Paul Frees

June 20, 1920 — November 2, 1986

Voice Artist

Boris Badenov, The Rocky and Bullwinkle Show

and many others

Stefanie Powers

November 2, 1942 —

April Dancer on The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. (1966)

Charles Sheffield

June 25, 1935 — November 2, 2002

Mathematician, physicist, author

President, Science Fiction Writers of America

President, American Astronautical Society

Chief Scientist, Earth Satellite Corporation

Behrooz Wolf series

The Heritage Universe

Cold as Ice

Chan Dalton

Jupiter

Supernova Alpha

Arthur Morton McAndrew

James Thurber

December 8, 1894 — November 2, 1961

Writer and cartoonist

Fables for Our Time & Famous Poems Illustrated (1940)

Further Fables for Our Time (1956)

Ray Walston

November 2, 1914 — January 1, 2001

Uncle Martin on My Favorite Martian (1963-1966)

The Master, Galaxy of Terror (1981)

Boothby, Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Voyager

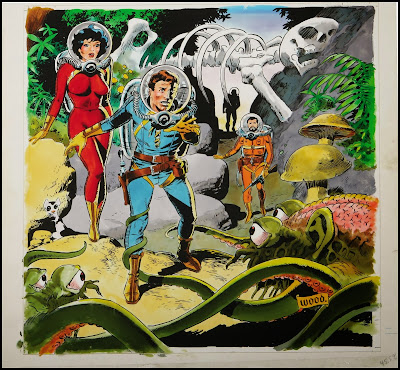

Wallace Wood

Here’s Hugo Award-winning comics artist Steve Stiles on Wallace Wood. He says it much better than I ever could.

Wallace Wood: The Tragedy of a Master S. F. Cartoonist, by Steve Stiles

My first introduction to Wallace Wood’s art was in 1956. I was twelve years old and had just walked into the neighborhood candy story, and there it was up on the rack with Little Lulu and Mighty Mouse; E.C.’s Incredible Science Fiction #33. The cover was by Wood, depicting a spacesuited figure against a backdrop of intricate and authentic looking machinery, all rendered in a crisp dramatic style. I was hooked and bought the magazine, becoming an instant E.C. fanatic from that moment on. I had no idea that the issue would be the last science fiction title that E.C. would publish, and that the company was on its last legs.

However, thanks to the local used bookshop in my neighborhood, I soon had a huge collection of back issues of E.C.s. Along with Jack Davis and Al Williamson, Wood was one of my favorites. I remember thinking how wonderful it must be to have all that talent, and that if only I could draw as well my petty problems would seem insignificant.

Years later I would get to meet Wally through friends who worked with him. I would learn more about him through articles and interviews in the fan press. And eventually I would realize just how wrong I had been.

Wallace Wood was born in 1927. After a stint in the Merchant Marines during wartime, Wood eventually arrived in New York he where studied art at Burne Hogarth’s Cartoonists And Illustrators School (later to become my alma mater, the School of Visual Arts). Soon he began work as a letterer in the comics field, moving up to assisting other artists, and by 1949 he had penciled and inked his first story, a romance, in My Confessions #7. Other work quickly followed, and by 1950 Wood was freelancing for numerous publishers like ACG, Standard, Avon, and Ziff Davis, illustrating Fu Manchu, Captain Science, Space Detective, and many others, collaborating on some stories with future DC Comics editor Joe Orlando.

1950 was also the year Wood’s talents would really develop at William Gaine’s Entertaining Comics. His first story, “The Werewolf Legend,” in Vault Of Horror #2, was done in collaboration with Harry Harrison, who would go on to become a science fiction writer (Stainless Steel Rat, Soylent Green). The team-up lasted for a handful of stories, until Gaines realized where the real artistic talent was, and Wood was off and running on a career with E.C. that (not counting MAD Magazine) would add up to almost 150 stories, from Frontline Combat to Piracy.

But it was his work for E.C.’s science fiction titles, Weird Science and Weird Fantasy, that would do the most to establish Wood’s reputation as the preeminent s.f. artist in the comics field. His brilliantly illustrated stories included many written by Ray (Mars Is Heaven) Bradbury, and were done in incredible detail, using techniques that utilized crafttint and scratchboard, with high-contrast inking techniques that drew the eye to each panel.

Such attention to detail, to utterly intricate machinery and startling aliens, was a strength of Wood’s art but also a considerable personal burden. Wood practiced a grueling work schedule that would’ve done in many an artist, habitually pulling all-night work sessions. It was a work pattern he would stick to all his life. One of his editors at E.C., Harvey (Mad, Two-Fisted Tales) Kurtzman, once commented that Wood devoted himself so intensely to his work that he burned himself out, adding “I think he delivered some of the finest work that was ever drawn, and I think it’s to his credit that he put so much intensity into his work at great sacrifice to himself.”

Wood’s other major work in the ’50s was a collaboration with Will Eisner on the famous “Outer Space” installments of The Spirit. By 1952 Eisner had become involved with projects involving the use of panel art as a teaching aid, forming his American Visuals Corporation, which led to Eisner’s work on the Army’s Preventive Maintenance (PM) magazine.

Despite help from Jules Feiffer and Jerry Grandenetti, Eisner was finding it difficult to supply pencils and inks to The Spirit. Wood was called in, and, with a growing public interest in space travel, Denny Colt was launched to the moon and back. Wood’s pencils and inks were a good match to Eisner’s own style, and his lunar landscapes were, in Eisner’s words, “terrific”. Unfortunately, the syndicates didn’t approve of a crime strip turning to science fiction, so Wood’s involvement lasted a little over nine episodes. Eventually the strips were reissued in a Kitchen Sink Press collection.

With the crash of comics in the mid-fifties, Wood turned to other freelance outlets, illustrating s.f. dust jackets, doing gag cartoons for men’s magazines, and working on advertising illustrations. He also helped Jack Kirby by supplying inks on his Sky Masters strip, and would later return to comics with inks for Kirby’s Challengers Of The Unknown (DC Comics).

From 1957 to 1960 Wood did numerous black and white wash paintings for H.L. Gold’s Galaxy magazine, illustrating stories by Randall Garrett and Frederick Pohl, to name a few. I may be biased in thinking that these represented Wood’s best work of that period; one of his double-page illustrations from Galaxy (The Man In The Mailbag) is hanging in my studio.

By the mid 1960s, Wood returned to comics with the Marvel revolution, supplying art for Daredevil and Dr. Doom. Some of these, like the Daredevil battle with Sub-Mariner, are fun to look at, but Wood’s strengths were not in drawing action scenes of battling superheroes. He was also becoming increasingly disgusted with the work-for-hire policies of the Big Two comics publishers, a system that reduced comics creators to mere cogs in a machine, isolating them from any real control and depriving them of many benefits.

Wood tried to establish more control over his own efforts by drawing and writing Tower Comics’ T.H.U.N.D.E.R. Agents and Dynamo and creating a number of new superheroes like Noman, Dynamo, Lightning, and Raven. As an editor, he also hired some fine talent, like Reed Crandall, Gil Kane, and Al Williamson. Impressive as some of the art was, it was a pale shadow of Wood’s work in his 20s, and compared to what Marvel was doing, Tower was rather lackluster. The titles were unsuccessful and, after less than two years, folded.

One of Wood’s assistants during the sixties was Dan (Dr. Strange) Adkins, a former science fiction fan who, together with Bill Pearson, had published a lavish fanzine, Sata Illustrated. “Dapper” Dan, as Stan Lee dubbed him, had often thought about publishing another fanzine, and, evidently infected Wood with the publishing bug. The result was Witzend, a photo-offset fanzine for fans and comics pros alike, featuring art and stories by Wood, Steve Ditko, Archie Goodwin, Ralph Reese, Reed Crandall, and a host of others. Wood published six issues through the late sixties. In many ways Witzend can be considered a forerunner of the independent small press publications that would come into being in later years. It was inWitzend that Wood first ran a new strip of his own, the Tolkein-inspired The Wizard Kings.

Kings.

By the 1972 Wood began doing work on strips for The Overseas Weekly, a publication for servicemen, writing and drawing Cannon (a sexy adventure strip) and Sally Forth (sexy humor). The third strip was Shattuck, a sexy western drawn by Howie Chaykin.

A hard life of overwork, heavy smoking, and alcohol abuse, as well as two failed marriages, were taking a toll on Wood. There seemed to be very little opportunity to work on decent s.f. stories in the limited comics world of the seventies. Wood still took on superhero work for both DC and Marvel, doing mostly inks, as well as drawing for Atlas/Seaboard, and Warren, but his dislike for the economic serfdom in the comics field grew along with increasing bouts of depression. By the late seventies Wood had suffered four strokes in addition to kidney problems.

Robbed of the ability to draw on his previous level of excellence and facing life on a dialysis machine, Wally Wood took his own life on November 2, 1981. He was only fifty-four years old.

Glenn Wood, Wally’s brother, and J. David Spurlock, Vanguard publisher and compiler of The Wally Wood Sketchbook, have set up the WALLY WOOD SCHOLARSHIP FUND for The School of Visual Arts in order to encourage and support young aspiring cartoonists and illustrators. Those interested in making tax-deductible contributions or further inquiries may contact:

Visual Arts Foundation

15 Gramercy Park South

New York, New York 10003