August 8th in Watergate History

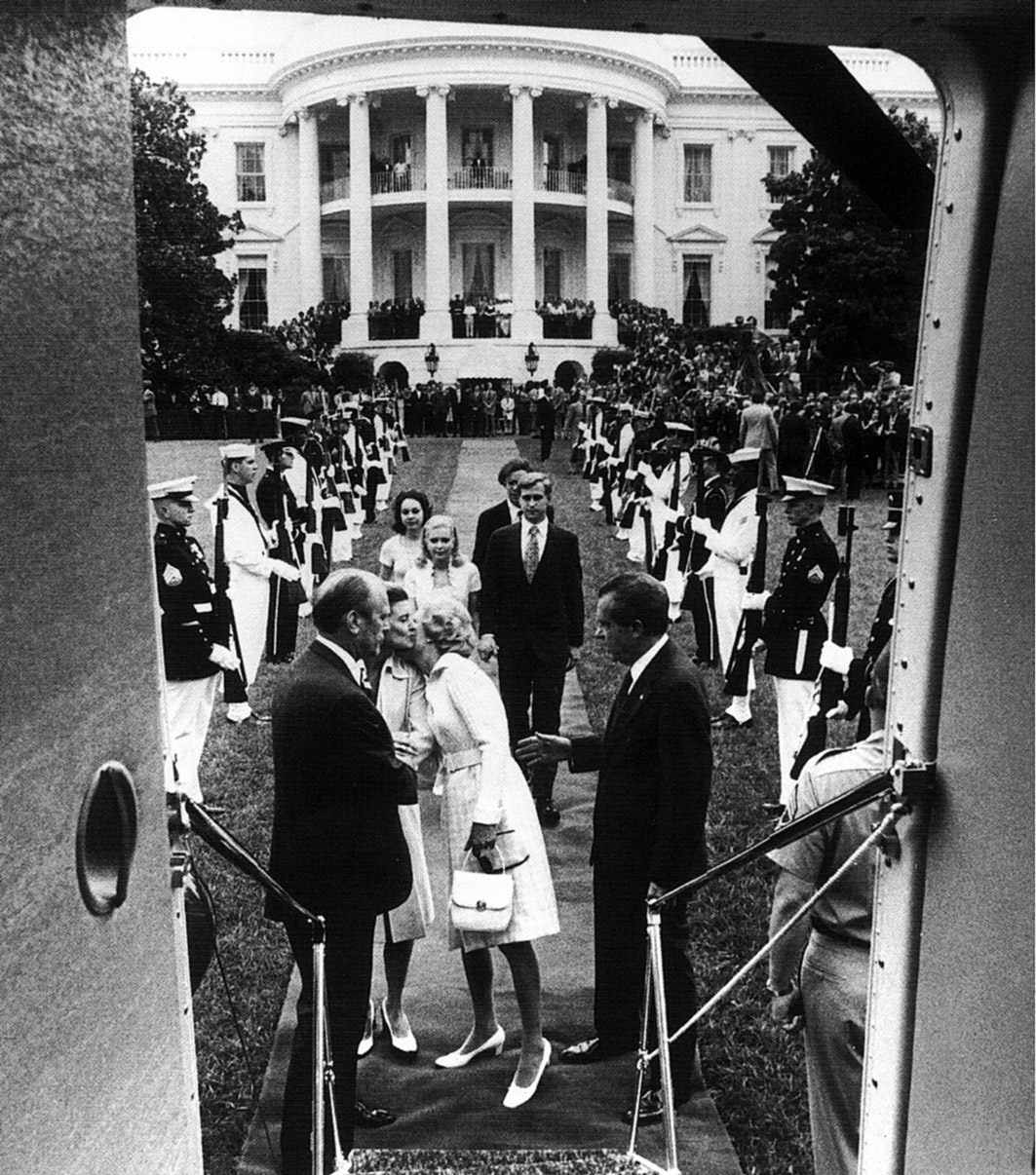

Richard Nixon leaves the White House following his resignation.

This post is taken from the Timespinner Press book Watergate Considered as an Organization Chart of Semi-Precious Stones, by Michael Dobson. Copyright © 2013, used with permission.

The Smoking Gun Goes Off

The Tipping Point

Until the tape revelation, much of the Watergate scandal had devolved into a “he said, she said” argument. There was no question that operatives associated with the Committee to Re-Elect the President had broken into the headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate office complex, but it was less clear how high up the scandal might reach. After all, the idea that low-level staff members might take it into their own heads to do something the boss would not approve is hardly unprecedented.

Initially, a lot of people believed that the “two-bit burglary” itself was simply a rogue staff operation, and that the cover-up was primarily designed to protect the Plumbers operation. Although parts of the story remain murky to this day, it now appears that the burglary itself originated at high levels of the Administration, and may have been ordered by Nixon himself, concerned about potential negative information possessed by DNC chairman Larry O’Brien.

Slowly, the chain of Watergate responsibility crept up the ladder, moving from CREEP to the White House itself, but the “smoking gun” that would implicate the President personally remained elusive. Although Dean’s explosive testimony had in fact implicated Nixon, it was still a matter of his word against that of the President of the United States.

Battle of the Tapes

The revelation of the White House taping system changed all that. The tapes themselves were capable of revealing once and for all “what the President knew and when he knew it.”

Nixon argued against the subpoena of the tapes for two reasons. The first was executive privilege, a claim based on the separation of powers and checks and balances enshrined in the U. S. Constitution. The second was a claim that the privacy of the tapes was vital to national security. In spite of losing several court decisions and conducting the Saturday Night Massacre, Nixon held fast to his position — as well he might, given the dangerous material on those tapes.

In April 1974, the House Judiciary Committee subpoenaed the tapes for 42 additional White House conversations. Nixon released edited transcriptions, still citing executive privilege and national security. Jaworski, about the same time, subpoenaed 64 tapes to support his criminal prosecutions of various Nixon administration officials.

The last word, of course, came from the Supreme Court. In late July 1974, it issued an 8-0 decision in United States v. Nixon: the subpoena was valid. Nixon had to release the tapes, and on them was what became known as the “smoking gun.”

The term “smoking gun” apparently first appears in the Sherlock Holmes story “The Gloria Scott,” but it gained its current meaning in the Watergate scandal. Roger Wilkins in the New York Times first used the term. “The big question asked over the last few weeks in and around the House Judiciary Committee’s hearing room by committee members who were uncertain about how they felt about impeachment was ‘Where’s the smoking gun?’”

My Gun Is Quick

On August 5, 1974, the House Judiciary Committee released what instantly became known as the “smoking gun tape.” It was a recording of a meeting that had taken place on June 23, 1972, six days after the original burglary, in which H. R. Haldeman, White House Chief of Staff, asked Nixon if he should ask Richard Helms, CIA director, to approach FBI chief L. Patrick Gray about halting his investigation on national security grounds. This, the special prosecutor and the Judiciary Committee agreed, constituted a criminal conspiracy to obstruct justice.

Here’s the relevant text:

HALDEMAN: …the Democratic break-in thing, we’re back to the–in the, the problem area because the FBI is not under control, because Gray doesn’t exactly know how to control them, and they have… their investigation is now leading into some productive areas […] and it goes in some directions we don’t want it to go. […] [T]he way to handle this now is for us to have Walters [CIA] call Pat Gray [FBI] and just say, ‘Stay the hell out of this …this is ah, business here we don’t want you to go any further on it.’”

NIXON: All right, fine, I understand it all. We won’t second-guess Mitchell and the rest. […] You call [the CIA] in. Good. Good deal. Play it tough. That’s the way they play it and that’s the way we are going to play it.”

Until that point, the ten Republican members on the House Judiciary Committee had voted against impeachment, but now they unanimously agreed that they would support an impeachment vote once the case reached the House floor.

In the American system, the impeachment of a President requires a simple majority vote of the House of Representatives, but removal from office requires a two-thirds vote of the Senate. In essence, this means that any removal of a President from office requires a substantial number of votes from the President’s own party. Impeachment can be a purely partisan act (see Clinton, Bill), but removal from office must necessarily be bipartisan.

Resigned to His Fate

It was therefore a delegation of Republican senators who informed President Nixon that there were only about 14 votes to keep him in office, far short of the 34 votes he needed. With the handwriting on the wall, Nixon took the only path available. In a nationally televised Oval Office address on the evening of August 8, 1974, Nixon resigned, saying:

“In all the decisions I have made in my public life, I have always tried to do what was best for the Nation. Throughout the long and difficult period of Watergate, I have felt it was my duty to persevere, to make every possible effort to complete the term of office to which you elected me. In the past few days, however, it has become evident to me that I no longer have a strong enough political base in the Congress to justify continuing that effort. As long as there was such a base, I felt strongly that it was necessary to see the constitutional process through to its conclusion, that to do otherwise would be unfaithful to the spirit of that deliberately difficult process and a dangerously destabilizing precedent for the future….

“I would have preferred to carry through to the finish whatever the personal agony it would have involved, and my family unanimously urged me to do so. But the interest of the Nation must always come before any personal considerations. From the discussions I have had with Congressional and other leaders, I have concluded that because of the Watergate matter I might not have the support of the Congress that I would consider necessary to back the very difficult decisions and carry out the duties of this office in the way the interests of the Nation would require.

“I have never been a quitter. To leave office before my term is completed is abhorrent to every instinct in my body. But as President, I must put the interest of America first. America needs a full-time President and a full-time Congress, particularly at this time with problems we face at home and abroad. To continue to fight through the months ahead for my personal vindication would almost totally absorb the time and attention of both the President and the Congress in a period when our entire focus should be on the great issues of peace abroad and prosperity without inflation at home. Therefore, I shall resign the Presidency effective at noon tomorrow. Vice President Ford will be sworn in as President at that hour in this office.”

The next morning, the President and his wife said goodbye to the White House staff and boarded a helicopter to Andrews Air Force Base, where Air Force One waited to fly them to his California home in San Clemente. He wrote later of his thoughts. “As the helicopter moved on to Andrews, I found myself thinking not of the past, but of the future. What could I do now?”

President Gerald Ford pardoned Nixon on September 8, 1974, saying, “[Watergate] is an American tragedy in which we all have played a part. It could go on and on and on, or someone must write the end to it. I have concluded that only I can do that, and if I can, I must.”

Nixon continued to maintain his innocence until his death on April 22, 1994.