October 25th in the Cuban Missile Crisis

Follow the inside story of the Cuban Missile Crisis as it evolves day by day from now through October 28!

Read: Yesterday Tomorrow Beginning of Series

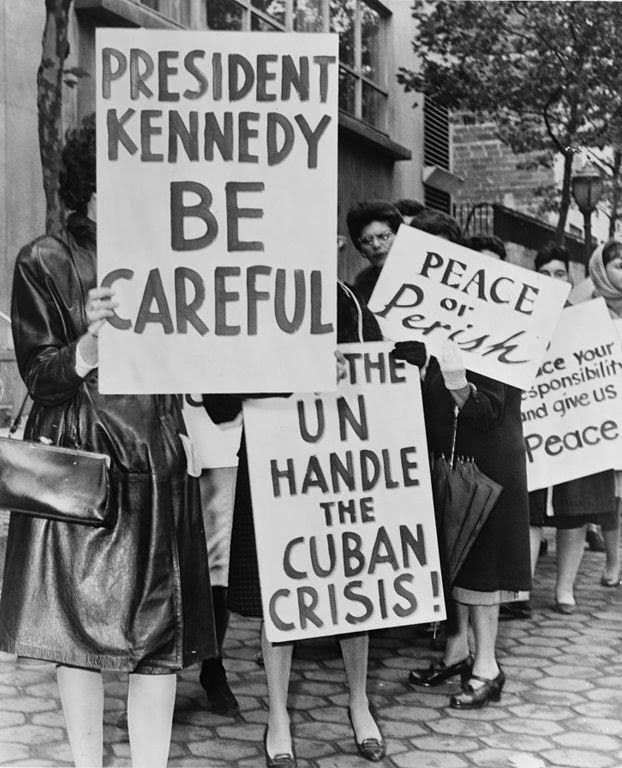

(Photograph: A group of 800 women from “Women Strike for Peace” demonstrate near the UN Building.)

“Until Hell Freezes Over!”

Thursday, October 25, 1962, was the tenth of the “Thirteen Days” Bobby Kennedy referred to in the title to his book about the Cuban Missile Crisis. It was on this day that the American public first learned of the missiles in Cuba.

As Castro prepared to defend his island and Khrushchev contemplated removing the missiles from the island, United States Ambassador to the United Nations Adlai Stevenson addressed the UN Security Council about the crisis. Stevenson was one of the few influential American leaders who favored solving the crisis through negotiation; he feared JFK was too willing to go to war. Nonetheless, he spoke against a backdrop of aerial recon photos of the missile sites, and when Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zornin stalled instead of answering Stevenson’s challenging question, the US ambassador famously declared that he was prepared to wait “until Hell freezes over” to get a reply. In reality, he knew that time was running out: A US invasion of the island was tentatively scheduled for October 30.

(You can listen to part of Stevenson’s speech on YouTube.)

Meanwhile, the Strategic Air Command (SAC) was at DEFCON 2. B-52 bombers were on airborne alert and taking up positions within striking distance of the Soviet Union; the B-47 medium bombers were being dispersed to various airfields and readied for rapid takeoff. Nearly 150 ICBMs were raised to ready alert, with another 160 nuclear-armed interceptors.

The CIA reported that Cuba was continuing to work on the missiles without interruption.

Meanwhile, 14 Soviet cargo ships about to enter the quarantine zone turned around and started home.

Text of Adlai Stevenson’s Address to the UN Security Council and to His Soviet Counterpart, Valerian Zorin: October 25, 1962

I want to say to you, Mr. Zorin, that I do not have your talent for obfuscation, for distortion, for confusing language, and for doubletalk. And I must confess to you that I am glad that I do not!

But if I understood what you said, you said that my position had changed, that today I was defensive because we did not have the evidence to prove our assertions, that your Government had installed long-range missiles in Cuba.

Well, let me say something to you, Mr. Ambassador—we do have the evidence. We have it, and it is clear and it is incontrovertible. And let me say something else—those weapons must be taken out of Cuba.

Next, let me say to you that, if I understood you, with a trespass on credibility that excels your best, you said that our position had changed since I spoke here the other day because of the pressures of world opinion and the majority of the United Nations. Well, let me say to you, sir, you are wrong again. We have had no pressure from anyone whatsoever. We came in here today to indicate our willingness to discuss Mr. U Thant’s proposals, and that is the only change that has taken place.

But let me also say to you, sir, that there has been a change. You—the Soviet Union has sent these weapons to Cuba. You—the Soviet Union has upset the balance of power in the world. You—the Soviet Union has created this new danger, not the United States.

And you ask with a fine show of indignation why the President did not tell Mr. Gromyko on last Thursday about our evidence, at the very time that Mr. Gromyko was blandly denying to the President that the U.S.S.R. was placing such weapons on sites in the new world.

Well, I will tell you why—because we were assembling the evidence, and perhaps it would be instructive to the world to see how a Soviet official—how far he would go in perfidy. Perhaps we wanted to know if this country faced another example of nuclear deceit like that one a year ago, when in stealth, the Soviet Union broke the nuclear test moratorium.

And while we are asking questions, let me ask you why your Government—your Foreign Minister—deliberately, cynically deceived us about the nuclear build-up in Cuba.

And, finally, the other day, Mr. Zorin, I remind you that you did not deny the existence of these weapons. Instead, we heard that they had suddenly become defensive weapons. But today again if I heard you correctly, you now say that they do not exist, or that we haven’t proved they exist, with another fine flood of rhetorical scorn.

All right, sir, let me ask you one simple question: Do you, Ambassador Zorin, deny that the U.S.S.R. has placed and is placing medium- and intermediate-range missiles and sites in Cuba? Yes or no—don’t wait for the translation—yes or no?

(The Soviet representative is waiting for translation. then responds) “This is not a court of law, I do not need to provide a yes or no answer…” (was cut off by Mr. Stevenson at this point) *Source United Nations Assembly video archives.

You can answer yes or no. You have denied they exist. I want to know if I understood you correctly. I am prepared to wait for my answer until hell freezes over, if that’s your decision. And I am also prepared to present the evidence in this room.

(The President called on the representative of Chile to speak, but he lets Ambassador Stevenson continued as follows.)

I have not finished my statement. I asked you a question. I have had no reply to the question, and I will now proceed, if I may, to finish my statement.

I doubt if anyone in this room, except possibly the representative of the Soviet Union, has any doubt about the facts. But in view of his statements and the statements of the Soviet Government up until last Thursday, when Mr. Gromyko denied the existence or any intention of installing such weapons in Cuba, I am going to make a portion of the evidence available right now. If you will indulge me for a moment, we will set up an easel here in the back of the room where I hope it will be visible to everyone.

The first of these exhibits shows an area north of the village of Candelaria, near San Cristóbal, southwest of Habana. A map, together with a small photograph, shows precisely where the area is in Cuba.

The first photograph shows the area in late August 1962; it was then, if you can see from where you are sitting, only a peaceful countryside.

The second photograph shows the same area one day last week. A few tents and vehicles had come into the area, new spur roads had appeared, and the main road had been improved.

The third photograph, taken only twenty-four hours later, shows facilities for a medium-range missile battalion installed. There are tents for 400 or 500 men. At the end of the new spur road there are seven 1,000-mile missile trailers. There are four launcher-erector mechanisms for placing these missiles in erect firing position. This missile is a mobile weapon, which can be moved rapidly from one place to another. It is identical with the 1,000-mile missiles which have been displayed in Moscow parades. All of this, I remind you, took place in twenty-four hours.

The second exhibit, which you can all examine at your leisure, shows three successive photographic enlargements of another missile base of the same type in the area of San Cristóbal. These enlarged photographs clearly show six of these missiles on trailers and three erectors.

And that is only one example of the first type of ballistic missile installation in Cuba.

A second type of installation is designed for a missile of intermediate range—a range of about 2,200 miles. Each site of this type has four launching pads.

The exhibit on this type of missile shows a launching area being constructed near Guanajay, southwest of the city of Habana. As in the first exhibit, a map and small photograph show this area as it appeared in late August 1962, when no military activities were apparent.

A second large photograph shows the same area about six weeks later. Here you will see a very heavy construction effort to push the launching area to rapid completion. The pictures show two large concrete bunkers or control centers in process of construction, one between each pair of launching pads. They show heavy concrete retaining walls being erected to shelter vehicles and equipment from rocket blast-off. They show cable scars leading from the launch pads to the bunkers. They show a large reinforced concrete building under construction. A building with a heavy arch may well be intended as the storage area for the nuclear warheads. The installation is not yet complete, and no warheads are yet visible.

The next photograph shows a closer view of the same intermediate-range launch site. You can clearly see one of the pairs of large concrete launch pads, with a concrete building from which launching operations for three pads are controlled. Other details are visible, such as fuel tanks.

And that is only one example, one illustration, of the work being furnished in Cuba on intermediate-range missile bases.

Now, in addition to missiles, the Soviet Union is installing other offensive weapons in Cuba. The next photograph is of an airfield at San Julián in western Cuba. On this field you will see twenty-two crates designed to transport the fuselages of Soviet llyushin-28 bombers. Four of the aircraft are uncrated, and one is partially assembled. These bombers, sometimes known as Beagles, have an operating radius of about 750 miles and are capable of carrying nuclear weapons. At the same field you can see one of the surface-to-air antiaircraft guided missile bases, with six missiles per base, which now ring the entire coastline of Cuba.

Another set of two photographs covers still another area of deployment of medium-range missiles in Cuba. These photographs are on a larger scale than the others and reveal many details of an improved field-type launch site. One photograph provides an overall view of most of the site; you can see clearly three of the four launching pads. The second photograph displays details of two of these pads. Even an eye untrained in photographic interpretation can clearly see the buildings in which the missiles are checked out and maintained ready to fire, a missile trailer, trucks to move missiles out to the launching pad, erectors to raise the missiles to launching position, tank trucks to provide fuel, vans from which the missile firing is controlled, in short, all of the requirements to maintain, load, and fire these terrible weapons.

These weapons, gentlemen, these launching pads, these planes—of which we have illustrated only a fragment—are a part of a much larger weapons complex, what is called a weapons system.

To support this build-up, to operate these advanced weapons systems, the Soviet Union has sent a large number of military personnel to Cuba—a force now amounting to several thousand men.

These photographs, as I say, are available to members for detailed examination in the Trusteeship Council room following this meeting. There I will have one of my aides who will gladly explain them to you in such detail as you may require.

I have nothing further to say at this time.

(After another statement by the Soviet representative, Ambassador Stevenson replied as follows:)

Mr. President and gentlemen, I won’t detain you but one minute.

I have not had a direct answer to my question. The representative of the Soviet Union says that the official answer of the U.S.S.R. was the Tass statement that they don’t need to locate missiles in Cuba. Well, I agree—they don’t need to. But the question is, have they missiles in Cuba—and that question remains unanswered. I knew it would be.

As to the authenticity of the photographs, which Mr. Zorin has spoken about with such scorn, I wonder if the Soviet Union would ask its Cuban colleague to permit a U.N. team to go to these sites. If so, I can assure you that we can direct them to the proper places very quickly.

And now I hope that we can get down to business, that we can stop this sparring. We know the facts, and so do you, sir, and we are ready to talk about them. Our job here is not to score debating points. Our job, Mr. Zorin, is to save the peace. And if you are ready to try, we are.

A Note on the ExConn Tapes

As noted previously, JFK had ordered a recording system to be installed in the Cabinet room, which he could operate by pressing a button under the table. As a result, virtually all ExComm meetings were recorded; these recording were released to researchers and the public only in the last decade or so.

While many people think that Richard Nixon was the first president to tape White House conversations, the practice went back to FDR. The biggest difference between Nixon’s system and those of his predecessors was that the Nixon system was fully automatic, and earlier systems were turned on and off at the President’s discretion.

You can listen to some of the actual recordings here. For transcripts of the recordings, look here.

Guest post by Douglas Niles, author of Final Failure: Eyeball to Eyeball, an alternate history of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Doug and I co-authored three alternate history military thrillers: Fox on the Rhine, Fox at the Front, and MacArthur’s War. He is also known for his fantasy novels and is an award-winning game designer.