July 13th in Watergate History

This post is taken from the Timespinner Press book Watergate Considered as an Organization Chart of Semi-Precious Stones, by Michael Dobson. Copyright © 2013, used with permission.

Let’s Go to the Tape, Johnny!

Waiter, There’s a Bug in My Soup

Richard Nixon, of course, was not the first president to tape conversations in the White House. I’ve read transcripts of secret tapes made by FDR while researching my novel (with Douglas Niles) MacArthur’s War, and have downloaded for my iPod the JFK tapes covering the Cuban Missile Crisis for another prospective alternate history with Doug Niles. (Doug went on to write it as a solo book, Final Failure.)

Eisenhower and Johnson also taped Oval Office conversations, but I haven’t heard any of them personally. New revelations from the Johnson tapes about Nixon and the Paris Peace Talks are addressed in the chapter “Origins of a Scandal,” earlier in this book. While it is certainly the case that no president after Nixon dared tape the Oval Office, from a historical perspective that’s quite a shame. FDR, Eisenhower, JFK, LBJ, and Nixon have all contributed hugely to the understanding of the presidency — and that’s a good thing.

Butterfield 8

Alexander Butterfield never planned to be part of a White House conspiracy, but by accident turned into one of the key figures in the scandal. A former Air Force pilot (he commanded reconnaissance aircraft during Vietnam), he retired from the USAF at the urging of college pal H. R. Haldeman, Nixon’s chief of staff, and became Deputy Assistant to the President, responsible for the daily business of the White House, including overseeing Nixon’s schedule.

In addition, Butterfield was responsible for maintaining Nixon’s historical records, and in that role he oversaw a secret taping system that Nixon had installed in the White House.

After Nixon’s reelection in 1972, Butterfield became administrator of the FAA. On July 13, 1973, members of Sam Ervin’s Senate investigation team interviewed Butterfield about his time in the White House. Previously, John Dean had mentioned that he suspected White House conversations were being taped, and so the committee staff routinely asked witnesses whether they knew if it was true.

Although Butterfield avoided revealing the taping system voluntarily, he had decided to tell the truth if asked directly. Ironically, it was the minority Republican counsel, Donald Sanders, who put the direct question to Butterfield, who replied that “[E]verything was taped … as long as the President was in attendance. There was not so much as a hint that something should not be taped.”

The significance of this was obvious, so the committee quickly scheduled Butterfield to appear before the full Senate committee on July 16, 1973, where chief minority counsel Fred Thompson (later part of the Law and Order television cast) asked the fatal question, “Mr. Butterfield, are you aware of the installation of any listening devices in the Oval Office of the president?”

Two days later, on July 18, 1973, Nixon ordered the tape recorders turned off.

There was no suggestion that Butterfield was part of the cover-up. He remained as FAA administrator until 1975. Butterfield, interestingly, was one of the few who guessed the real identity of “Deep Throat,” telling the Hartford Courant in 1995, “I think it was a guy named Mark Felt.”

Tape Worm

Only about 200 hours of the 3,500 hours of conversation recorded on the Nixon tapes even mention Watergate, but eight of the tapes were immediately subpoenaed by Special Watergate Counsel Archibald Cox. Citing executive privilege, Nixon refused. When Cox did not back off, Nixon ordered his attorney general, Elliot Richardson, to fire him. Richardson refused and resigned, as did his deputy William Ruckelshaus. It fell to the Solicitor General, Robert Bork, to fire him in what became known as the “Saturday Night Massacre.”

That was hardly the end of the taping problems. Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods, made a “terrible mistake” and erased five minutes of the June 20, 1972, recording. Strangely, the gap grew from five minutes to 18-1/2 minutes. Woods denied she had anything do to with the additional 13 minutes.

While only the participants know for sure what was discussed in those missing 18-1/2 minutes, H. R. Haldeman’s notes say that in that particular meeting, Nixon and Haldeman spoke about the arrests at the Watergate that had taken place three days previously.

Although various attempts were made to explain away the gap, the President’s attorneys eventually decided that there was “no innocent explanation” they could offer for the problem.

In any event, it wasn’t the 18-1/2 minute gap from June 20 that was the problem, but rather the tape of June 23, six days after the break-in, that would prove Nixon’s undoing, covered later.

Unlike previous Presidential taping systems, the Nixon system was automatically activated by voice. Previously, the President had to manually activate the taping system by flipping a switch. Of course, no sensible president would voluntarily tape himself talking about potentially criminal actions, but in the case of Nixon, the automated nature of the tapes suggested that if he had indeed made self-incriminating statements, they would be on the tapes.

The tapes were a godsend for John Dean. The all-too-obvious flaw in Dean’s testimony was that it was his word against the President of the United States. But if the tapes confirmed what Dean was saying, it would substantiate his testimony. Accordingly, Archibald Cox, the Watergate Special Prosecutor, issued his subpoena.

Tape Dancing

Nixon initially refused to release the tapes on the Constitutional grounds of executive privilege and the separation of powers, then added another claim that the tapes were vital to national security. In October 1973, under increasing political pressure, Nixon offered a compromise in which he would allow Mississippi Democratic Senator John Stennis to review and summarize the tapes, and report his findings to the Special Prosecutor. Cox rejected this.

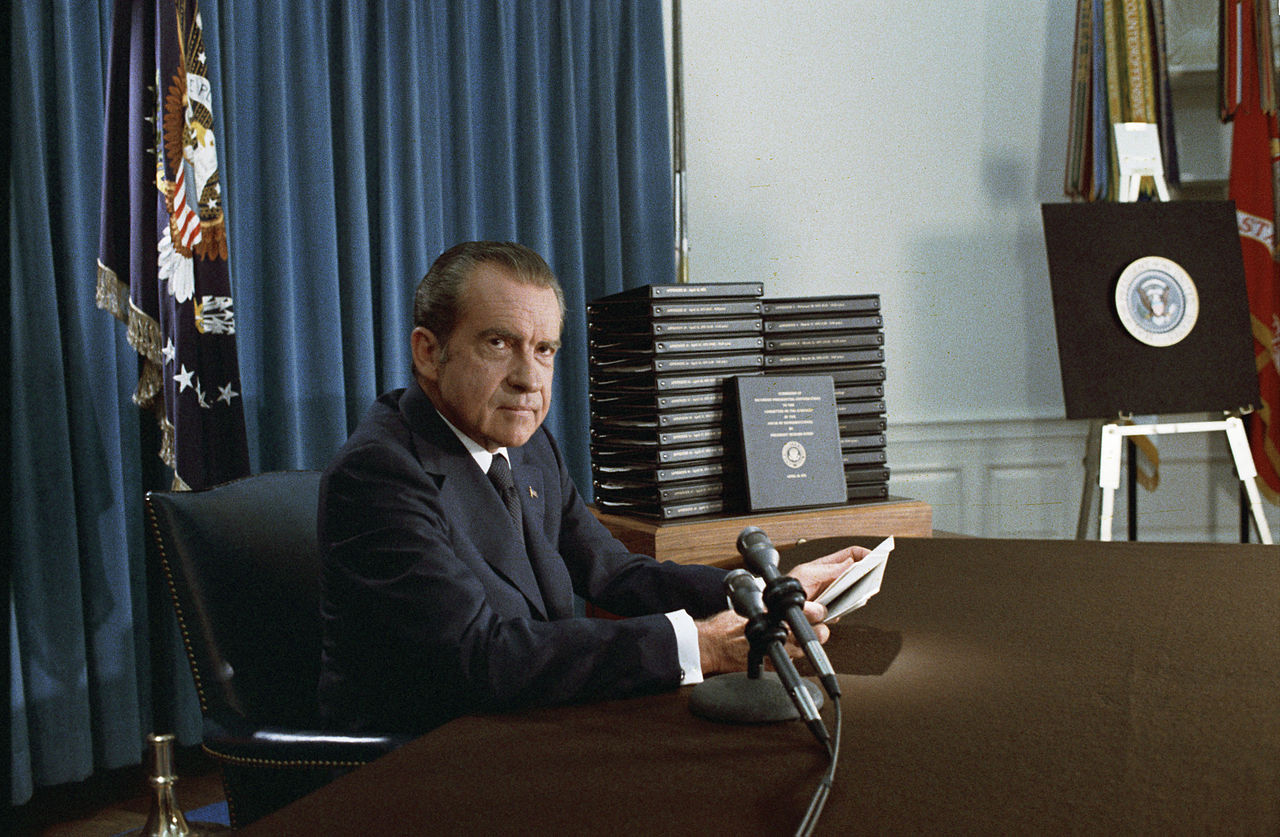

Even after Cox was fired in the Saturday Night Massacre, the pressure to release the tapes continued, and Nixon was forced to appoint a new special prosecutor, Leon Jaworski. As 1974 began, bad news for the Nixon Administration began to mount. In April, Nixon decided to release typed transcripts of the relevant tapes, from which the infamous phrase “expletive deleted” originated.

Nixon was too late. All the juicy parts of the transcripts were published by Washington columnist Jack Anderson, who managed to get hold of them before Congress did.

You Heard It Here First, Folks

While I rely mostly on secondary sources, I do actually have one original piece of Watergate information. One of my neighbors (our mortgage broker, actually), was Laurie Anderson, daughter of “Washington Merry-Go-Round” columnist Jack Anderson. She told me how Anderson’s newspaper column got the transcripts before the Senate did. It seems that Anderson had a White House janitor on his payroll, who fished the single-use carbon paper out of the trashcans and delivered it to Anderson. Laurie told me how she taped the carbons to a lampshade and typed up the contents for her father.

United States v. Nixon

Meanwhile, the court case made its way to the Supreme Court. On July 24, 1974, in the case United States v. Nixon, the court ruled unanimously (with justice William Rehnquist recused because he had formerly worked for Nixon’s Justice Department) that the tapes should be released. Six days later, on July 30, Nixon complied.

The transcripts indeed confirmed Dean’s testimony.