Christmas in History

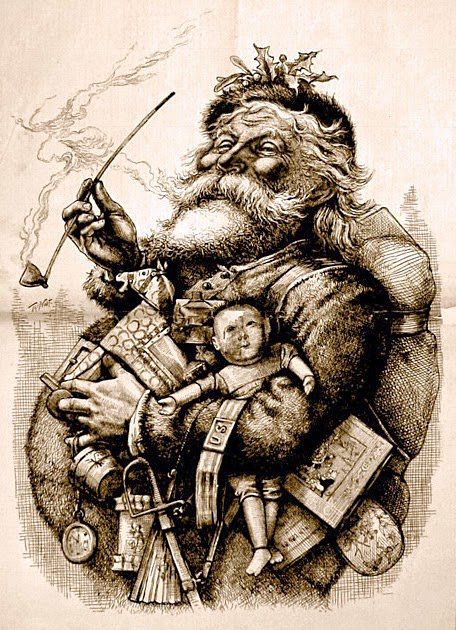

Merry Old Santa, Thomas Nast

In the absence of birth certificates (short form or long) or contemporary newspaper listings, there’s little historical evidence for December 25 as the actual date of birth of the historical Jesus of Nazareth. References to shepherds watching their sheep at night suggests a spring birth, not a winter one. Biblical references linking the chronology of Jesus to that of John the Baptist argue for a fall birth. The early Christian scholar Clement of Alexandria summarizes arguments for potential dates including March 21, April 15, April 21, and May 20.

In any event, the idea of the birth of Jesus being celebrated on December 25 doesn’t begin until the fourth century. (Orthodox Christians, who use the earlier Julian calendar rather than the Gregorian calendar for liturgical purposes, normally celebrate Christmas on January 7, which is the equivalent of Julian December 25.)

Why December 25? Well, holidays that roughly coincide with the Winter Solstice, the shortest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere, are as old as civilization. The Solstice normally occurs on December 21 (occasionally on December 22), and by December 25, astrologers were able to notice a slight increase in the length of days, evidence that the world would not (this year, at least) be plunged into eternal darkness.

In Rome, the solstice was celebrated by Saturnalia, a festival honoring the deity Saturn. It began on December 17 and ran through December 23. December 17 was also the first day of the astrological sign of Capricorn, which was in the house of Saturn. The Greek winter holiday of Brumalia (associated with Dionysus) covered roughly the same time period.

December 25 itself was an important holiday, Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the birthday of the unconquered sun. The Zoroastrian god Mithra (sometimes Mithras), who was quite popular with Roman soldiers, was born of a virgin on December 25 (other versions say he was born from a rock) and sent by Ahura-Mazda to save the world. This festival was made an official Roman celebration under the reign of the emperor Aurelian, and some historians argue that the choice of December 25 was meant to co-opt and Christianize an existing holiday.

Malachi 4:2, considered one of the prophecies of the eventual birth of the Messiah, reads, “But for you who revere my name the sun of righteousness shall rise, with healing in its wings.” It’s easy enough for the festival of the “sun of righteousness” to be switched from the virgin birth of Mithra to the virgin birth of Jesus. A 12th century Syrian bishop named Jacob Bar-Salibi endorsed this theory, writing, “It was a custom of the Pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the Sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnised on that day.”

However, there’s another argument, championed by the Church of England’s Liturgical Commission, among others. In Jewish belief, it was traditional that great men lived a whole number of years, without any fractions. The date of the conception of Jesus, therefore, would have to be the same date of his death. The New Testament account of the crucifixion says that Jesus died on a Friday at the beginning of Passover, and was resurrected the following Sunday. This would put the date as either 14 or 15 Nisan in the Hebrew calendar.

It’s difficult to convert that date with any accuracy into a corresponding Julian year (calendar conversions in general are tricky, especially because the Hebrew calendar is lunisolar and the Julian/Gregorian calendar is solar). In any event, if Jesus died on 14/15 Nisan, he would, in this tradition, have been conceived on the same date.

The Hebrew month of Nisan is important for other reasons. The early 2nd century scholar Rabbi Eliezier writes, “In Nisan the world was created; in Nisan the Patriarchs were born; on Passover Isaac was born…and in Nisan they [our ancestors] will be redeemed in time to come.” Around 200 CE, Tertullian, sometimes called “the founder of Western theology,” calculated that 14 Nisan in the year of the Crucifixion worked out to March 25 in the Roman calendar. If that was also the date of the conception of Jesus, add exactly nine months and you have December 25 as the date of birth.

Of course, it might just be happy coincidence that the Jewish theological argument just happens to put the birth of Jesus on the date of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, but of such arguments theology is made.

Roman imperial silver disc of Sol Invictus, 3rd Century

With various Fox News screeds about the so-called “War on Christmas,” you’d think that Christmas had always been a special day among Christians, but that turns out not to be the case. It’s not until 354 CE that any mention of a festival or even a religious service commemorating the birth of Jesus shows up. Earlier Christian writers argued strenuously against it. In the 3rd century, one writer commented that the Bible only mentioned sinners as celebrating their birthdays, and another actively ridiculed the idea of celebrating the birthdays of gods. Easter was the important celebration, on the grounds that the death and resurrection, not the birth, was the event of great theological worth.

Regardless of the reason for the establishment of December 25 as the birthday of Jesus, it’s very clear that the celebration of the season took its cues from the Roman festivals surrounding it. It was hardly a kid-friendly event, but rather a drunken carnival. Some Christian sects discouraged or even forbade the celebration of Christmas on the grounds that it was unbiblical. In the early Middle Ages, Epiphany was a much bigger deal that Christmas.

It’s generally known that many of the symbols of Christmas as we know it borrowed from pre-existing pagan traditions. As Christian missionaries brought their new religion to other lands, they shrewdly coöpted existing symbols and traditions as a way to ease people into the new worship. Holly was used as winter fodder for livestock in England and Wales. Ivy was used in Greek and Roman religious ceremonies.

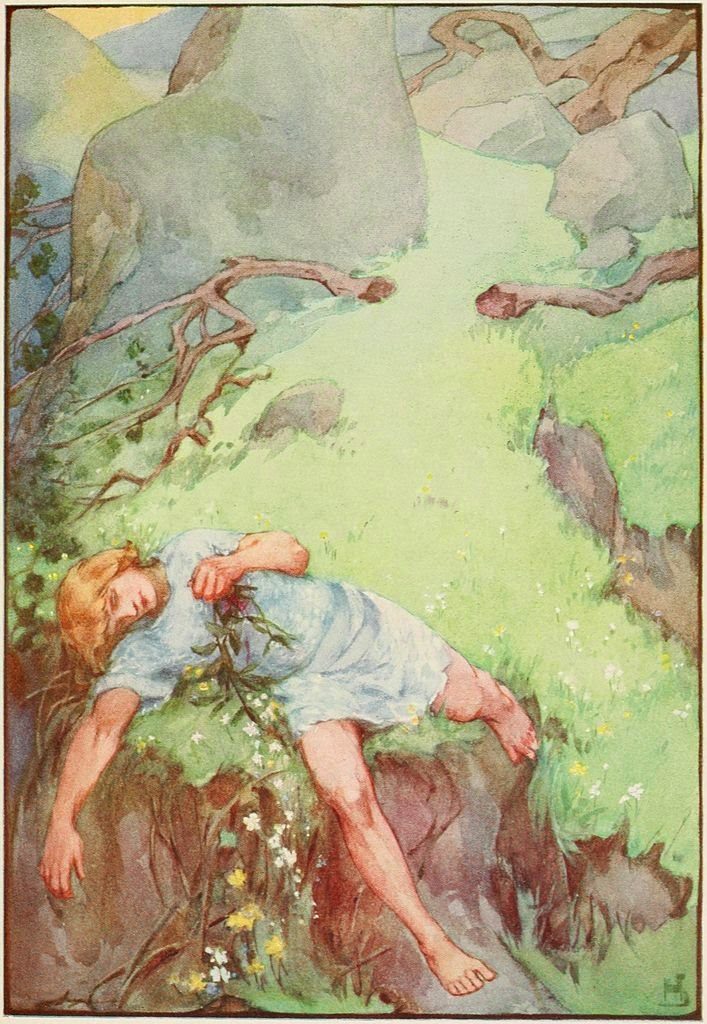

Mistletoe was sacred to Druids, and played a special role in the death of the Norse god Baldur. When a prophetess told Odin that Baldur would meet his doom, Odin solicited oaths from all things that they would not harm Baldur, forgetting only the small and harmless mistletoe. For sport, the gods threw various objects at Baldur—sticks, rocks, and spears, and laughed as they bounced off him.

Loki, jealous as usual, discovered the mistletoe exception and tricked the blind god Hodr into throwing a shaft of mistletoe at Baldur, killing him. Odin sent another of his sons, Hermod, to Hel, goddess of the underworld, to obtain the release of Baldur. Hel responded, “Then let every thing in the cosmos weep for him, and I will send him back to you. But if any refuse, he will remain in my presence.”

Everybody did weep for Baldur, with one exception, a giantess (who turned out to be Loki in disguise). Baldur remained with Hel until Raganrok, and when the world was destroyed and recreated, he was resurrected to bless the world and its inhabitants.

The death of Baldur, from A Book of Myths (1915)

The Twelve Days of Christmas had their origin in the Yuletide, also twelve days in duration. While “Yule” is often thought of as simply another word for Christmas, it was a German midwinter festival that began on the Solstice. It also had Norse roots; another name for Odin was Jólfaðr, or Yule Father. The Yule log and the Yule boar (which became the Christmas ham) were part of that tradition. There were also Yule goats, possibly a reference to Thor’s chariot, which was pulled by goats. Some early traditions have Father Christmas riding a goat rather than being pulled by reindeer. In fact, in Scandinavia, the goat was the giver of Christmas gifts, which gives “getting one’s goat” a whole different meaning. (In Wiccan Solstice celebrations, the rebirth of the Great Horned Hunter God has echoes of the Yule goat tradition.)

Father Christmas on the Yule Goat

While the so-called “War on Christmas” is mostly made up, there was an actual war on Christmas that was successful for a time. During the Interregnum in England, when a Puritan Parliament ruled, Christmas was banned as “a popish festival with no biblical justification” beginning in 1647. In its place, Parliament decreed a day of fasting. Pro-Christmas riots broke out in several cities, but it wasn’t until the Restoration in 1660 that the ban officially ended. Puritans in New England similarly disapproved of Christmas, and its celebration was banned in Boston from 1659 to 1681. (To this day, Jehovah’s Witnesses; Messianic Jews; most Sabbatarian denominations; the Iglesia ni Cristo; the Christian Congregation in Brazil; the Christian Congregation in the United States; and some Independent Baptist, Holiness, Apostolic Pentecostal, and Churches of Christ congregations still do not observe Christmas as a religious holiday.)

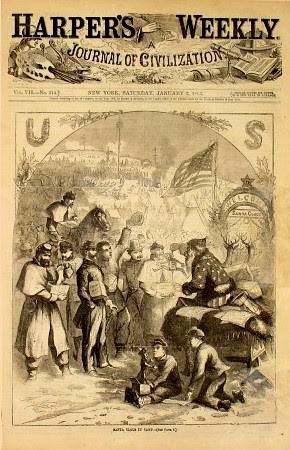

Even at the time of the American Revolution, Christmas was not widely celebrated in the United States. George Washington famously used Christmas Night as an occasion for a sneak attack on Hessian forces at Trenton. The first active Christmas celebrations in US history began during the American Civil War—Union soldiers wrote about decorating their camp Christmas trees with salt-pork and hard tack. Arguably the biggest Christmas present of the war came from US General William Tecumseh Sherman, who famously sent a telegram to President Abraham Lincoln following the end of his March to the Sea that read, “I beg to present you as a Christmas gift, the city of Savannah, with 100 and 50 guns and plenty of ammunition, also about 25,000 bales of cotton.”

Alabama was the first US state to declare Christmas a legal holiday in 1836. The US Congress first declared Christmas a Federal holiday in 1870. Oklahoma was the very last US state to get with the program; Christmas became an official holiday there in 1907.

The Victorian Era saw a resurgence and reinvention of Christmas, and it is only in the 19th century that Christmas begins to take on its familiar outlines. Charles Dickens, in A Christmas Carol, reconstructed Christmas as a family-centered event. Previously, English and Dutch Christmas celebrations primarily involved groups of young men going house to house demanding alcohol and food—trick or treating sans costumes. For the first time, Christmas began to be a holiday centered around children.

“Scrooge and the Ghost of Marley” by Arthur Rackham, 1915

Early Dutch settlers in New York considered St. Nicholas (“Sinterklaas”) to be their patron saint and hung out stockings on December 5, St. Nicholas Eve. Washington Irving wrote of Sinterklaas that he had a wagon that could ride over the tops of trees to bring presents to children. In 1821, an anonymous poem about “Santeclaus” added the sleigh, although at the time it was pulled by a single reindeer.

Besides Dickens, probably no source is more responsible for today’s Christmas than Clement Clarke Moore, author of “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” popularly known as “The Night Before Christmas.” Moore, a New Yorker, was familiar with St. Nicholas traditions, but his own description quickly overwhelmed all other portrayals. Cannily, Moore moved the events from the theologically problematic Christmas Day to the less sensitive Christmas Eve.

The modern Santa Claus takes his appearance from a cartoon by Thomas Nast, published as the cover of Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863. Nast continued to evolve his Santa Claus image into the more familiar version that heads this article.

Thomas Nast’s Santa Claus, Harper’s Weekly, January 3, 1863

That pretty much takes us to the present day, or the Present Day. People continue to argue about the relative importance of the religious Christmas to the essentially secular one, though as we’ve seen, even among Christians, reverence for Christmas is hardly universal.

The secular tradition is, by contrast, unassailable. From the adaption of Norse and Germanic symbols, the 17th century English pro-Christmas riots, and the adaptation of the Dutch Sinterklaas into the modern Santa Claus, Christmas has evolved into the quintessential children’s holiday, a symbol of the world’s rebirth in Sol Invictus.

Happy Christmas to all, and to all a good-night!

“Horse Drawn Sleigh,” Currier and Ives